BUT HERE WE ARE

Project in Post-Production

Synopsis

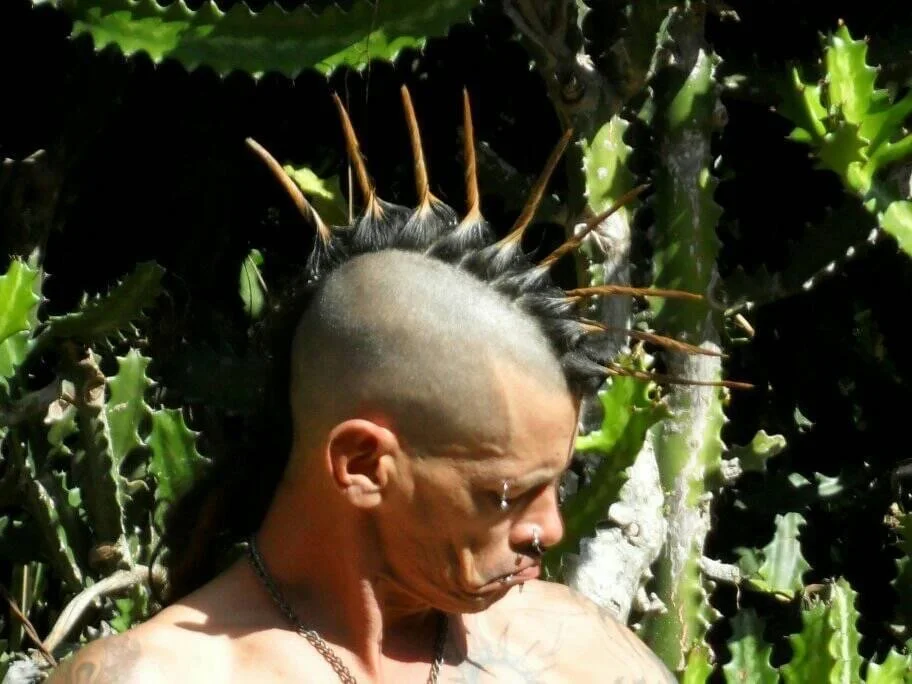

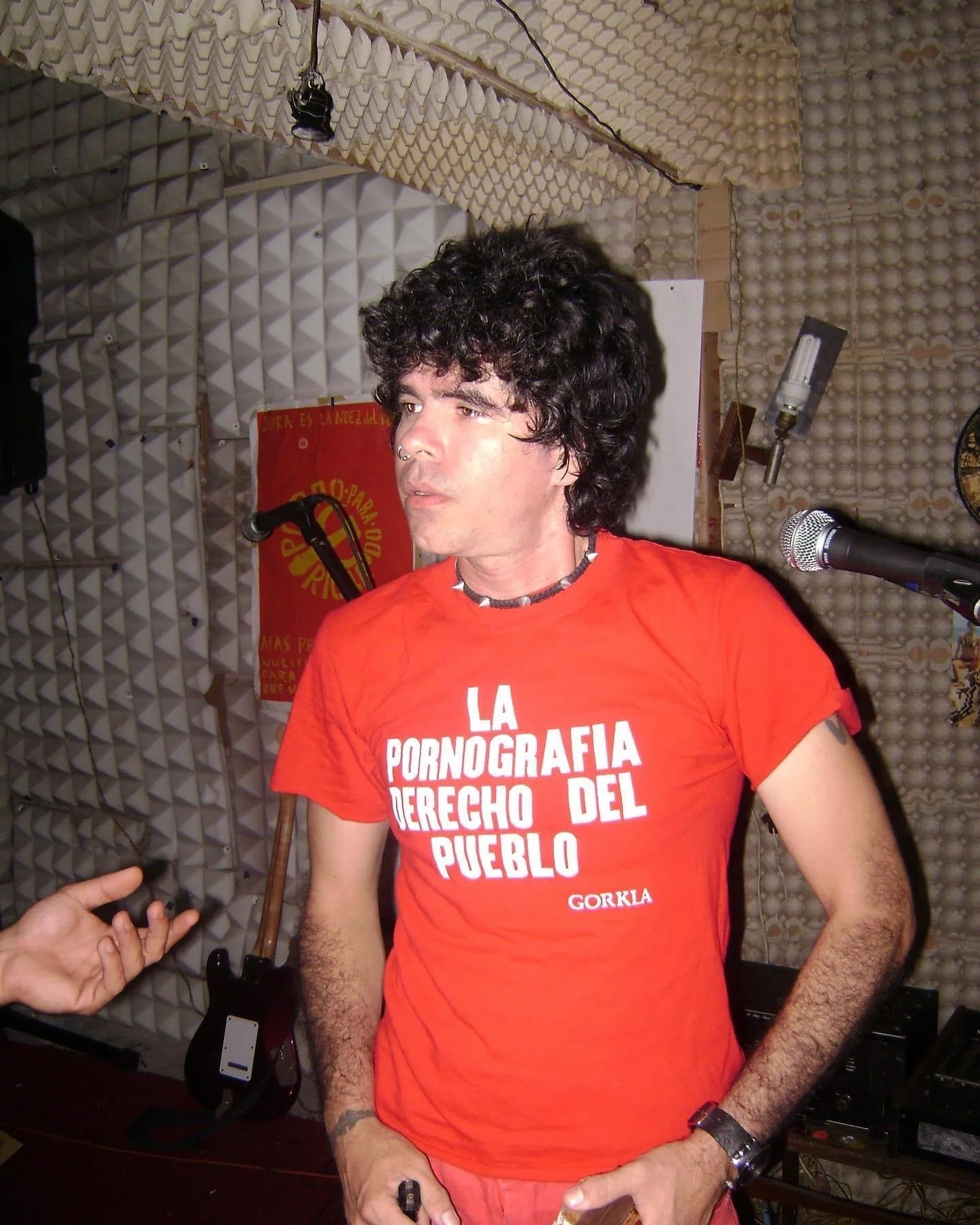

The film moves in interplay between the individual and society, or to be more precise, between an established social system and the individual rejection of this system. In specific terms, it is about punk musicians in Cuba: a strongly repressive system that fundamentally prohibits punk songs because of “contra-revolutionary agitation” and puts musicians in jail if they give illegal concerts or even mess with the police. It portrays people who are looking for a form of existence while rejecting the mainstream. It shows the true nature of the punk musicians and their lives in Cuban reality. It takes a look behind the cliché, behind the façade. It gives punk a face, a social reality, and offers viewers the opportunity to distance themselves from or identify with it. The film aims to capture this form of existence as diversely as possible and without judgement.

The film is not a reportage, but rather a study of everyday life. It focuses on the people and shows us the way they live. Behind the punk music – the credo of the film – are people who try to express themselves through their lyrics and songs. However, the film does not primarily want to be a music film, but rather collect evidence of a critical, partially rebellious attitude towards the state and established society. What kind of people are they? What is their view of the world, their image of humanity? What do they dream of; what exactly makes them angry? Among the various punk musicians, I would like to approach those who are politicised and who, with their entire existence, seek resistance and take a risk. What is expressed in this marginal music, controlled and suppressed by the state law enforcement agencies? Anarchy? One last bit of resistance? A rebellious nature? The desire to provoke? An existential need to communicate? One of their lyrics is: “No nos quieren ver pero aquí estamos.” (“You don’t want to see us, but here we are.”)

Advertising has monopolised punks and turned them into the cliché of non-conformists. Many associate punk with rash provocation, marginalisation and drug addiction. This may be so in individual cases, but overall it is prejudice. These prejudices may be a defence reaction to avoid showing consideration for the musicians’ inspiration. In any case, the film tries to recognise and make this inspiration visible and, if possible, to make it comprehensible. But it also tries to grasp the margins of the punk musicians, the limited radius of their sphere of influence. The film goes where very few of us go. And from there, it looks back and at the world – at us.

Author’s notes

For my second documentary, “The Future is Today”, as well as for my third film “Claroscuro”, I filmed two concerts, which the person portrayed in each film visited respectively. When editing, I noticed how extensive the material was and how much I liked this specific ambience of the musicians; how there was attraction and curiosity. For a long time, rock and, more particularly, punk music remained something forbidden yet fascinating to me; an alternative world to the bourgeois, harmless universe of my parents. In fact, my parents didn’t let me go to concerts when I was a teenager, they were afraid that I would end up in a bad group. Although I visited this alternative world and got to know it a little over the course of time, I was never really immersed in it. I never really gained an objective perspective on it or dealt with the topic. Of course, I secretly sympathised with the punks because I liked their courage and lack of concern, their scathing humour and their subversiveness, but I never got involved with them.

In Cuba, I went to the five or six best-known punk bands and spent several days with each of them, had conversations and filmed rehearsals. I want to immerse myself even more in the everyday life of the band members and get even closer to the real world – but that takes a lot of effort, since the bands are spread across the island. Instead of the music itself, I am more interested in the musicians, the people and their lives, which are expressed in punk music. At the same time, I am interested in sifting through archive material in order to capture the Cuban punk movement in its history, which is still young. I find it quite interesting that it took many years for punk to gain a foothold in Cuba. It only happened in 1991, 14 years after the “Sex Pistols” started punk. Does that say anything about state control of information? Or are there other reasons for this?